by Fleshtone Staff

Home is an online exhibition curated by Claudia S. Preza. The exhibition was a dive into how quarantine affected the global artist community. While it features artwork made during the stay at home orders, there were a few relevant older works which were included. It’s a tribute to hope, bonding, and immersion. It is a testimonial to the unhinged, uneasy, and deeply insecure feelings that have engulfed the nation. While artists are usually regarded as vanguards, this show is proof that art has its limitations. If society still turns it’s back to the most vulnerable is it possible or even inevitable that artists will do the same. How do we responsibly handle the narratives of the neglected?

The virtual space is large and expansive with significant distance between each artwork. This makes the motion of moving forward through the show a slow and deliberate process. The pace matches the burden of what has been an overabundance of alone time for most. Burdened by the restraints of quarantine, the arrangement influences the audience to indulge for bit. One piece at a time.

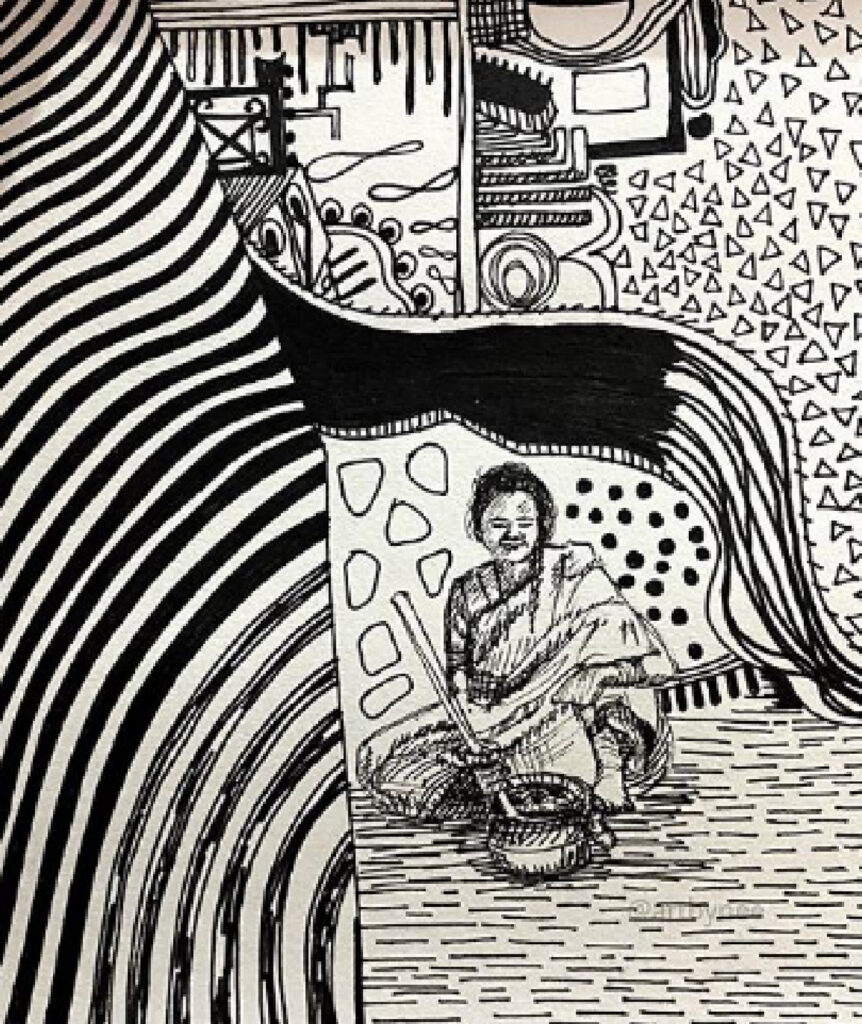

It’s especially effective in displaying the work of Nidhi Garg’s “Quarantine Days” series. The repetition of marks and patterns meshed with little moments of humanity captures the time, boredom, and yearning of quarantine. Garg’s work is a doodled style of black and white design that harkens back to drawings in the margins of school notes. The essence of youth and boredom at this time is encapsulated in the repetitive marks. Documenting her emotions during the ritual and chaos of COVID, the ink drawing challenges us to re-conceptualize how we experience the seasons of life as linear.

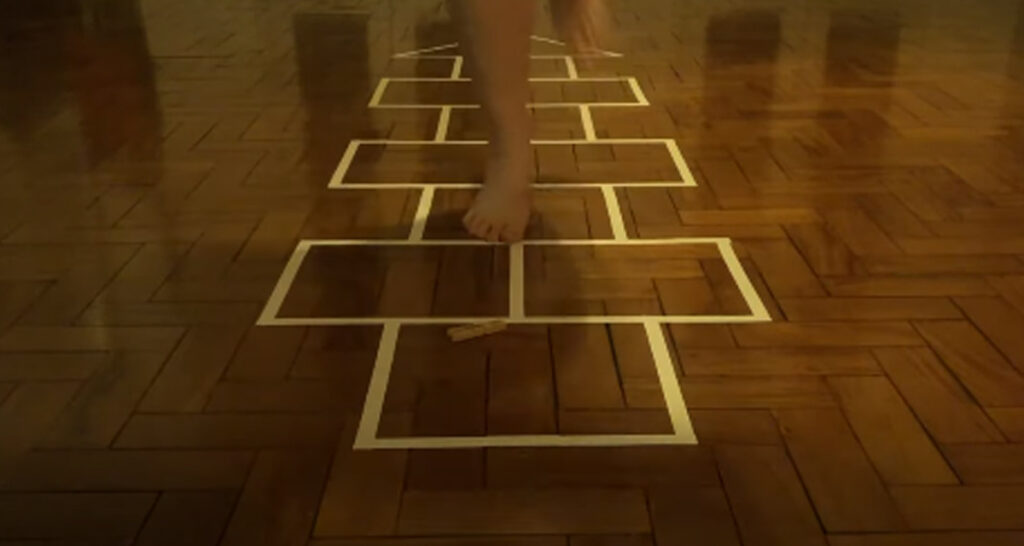

Another pivotal artist in Home, Tamara Ganem, also employs elements of age. Documenting the repetitive passage of time, we see her methodically playing hopscotch in her video Trying to get to heaven before they close the door. Ganem accentuates how ritualistic the childhood game of hopscotch is by carefully playing in silence. Originally, hopscotch was a training activity for Roman soldiers. It was a 100 foot long course used to increase dexterity and vigor. Children from the British Isles watched and gamified the military ritual as Rome occupied the land. Ganem has used childhood rituals and free time practices to control and pass time. The replication of this game process by Ganem emphasizes the youthfulness and problem-solving emerging from quarantine.

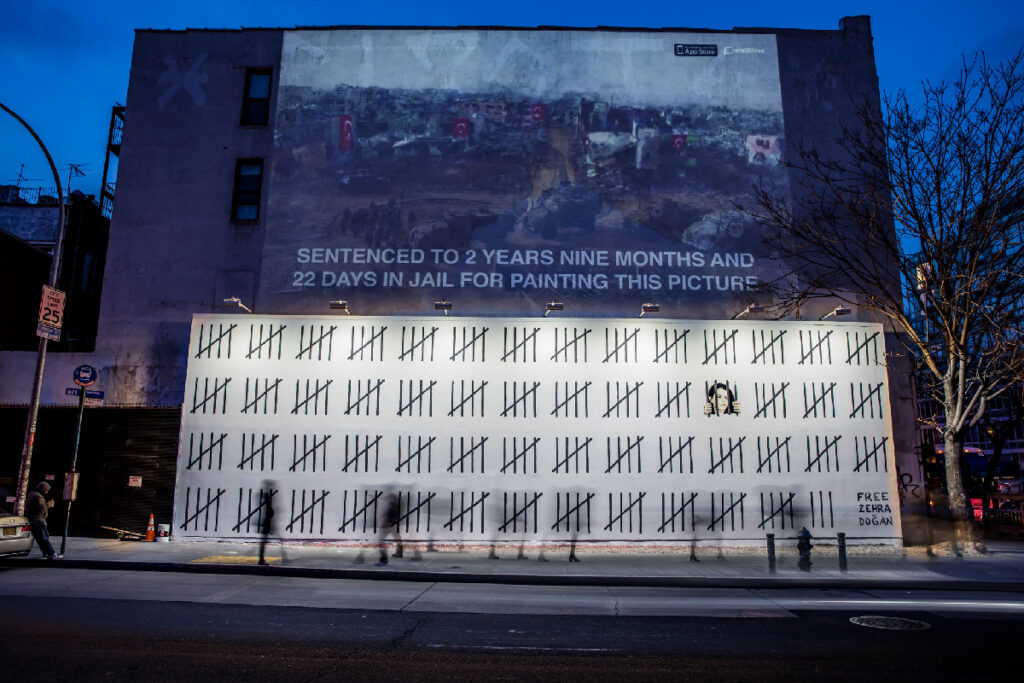

The same treatment to time and endurance gets used in Maria Mazzillo’s pieces Quarantine and Quarantine Day 65. The video of Mazzillo’s hands from her point of view documents the process and is shown next to a still photo of the piece. Painted red fingernails stab through black fabric covered in red beads that form tally marks. The needle pushes through in the place where the next bead is attached. Another red tubular bead is then threaded through and embroidered on. The beads make marks that are a testament to the number of days spent in quarantine and the process evokes a sense of longevity and endurance. The form calls to mind the imagery of a person in prison counting down days to freedom on the wall of a prison cell. Mazzillo is not the first or last artist to use this symbol of diligence and waiting yet her handling of it is questionable.

To see how these forms are handled otherwise, observe Banksy’s 2018 piece Free Zehra Dogan that appeared in New York City in 2018. The work covered the expanse of the Houston Bowery Wall. Banksy uses the imagery of tally marks to depict the days Turkish artist Zehra Dogan, was imprisoned for painting a watercolor of a town demolished by the Turkish Government in 2015. The notable difference between Banksy and Mazzillo’s use of tally marks is that Banksy advocated for the release of an imprisoned person who no doubt suffered innumerable transgressions at the hands of her captors. Dogan was released on February 24, 2019 after two years, nine months, 22 days in Turkey’s Tarsus Closed Women’s Prison. Mazzillo is in the comfort of her home laminating on not being able to go outside. There’s a marked difference in privilege and experience. Mazzillo’s days spent in quarantine are incomparable to the imprisonment of millions across the globe. She’s wearing fingernail polish and embroidering. Brazil, where the video originated, has prisons where violence is not a question of if, but when. For artists to use the charged imagery of imprisoned people to talk about being at home is callous.

Elevated curatorially, Mazzillo’s art is exhibited twice, side by side, as both video and photo format. Other artists have multiple works featured, but no repeat display of the same object. Quarantine Day 65 is on display in a superior room that departs from the rest of the exhibition’s level and blue walls. An analysis of this space could say that the inlet mimics feelings of entrapment and isolation but the elevation of the space counters that interpretation by giving it an exalted feeling. The works in this area feel special and exceptional.

The narrative that quarantine is like prison is first introduced in the opening wall text and catalog written by Preza. “Furthermore, they [the artists] showcase how isolation created a haven and a prison…” Let’s talk for a second about how people in prison are experiencing a global pandemic with the rest of us. Artists are creating in the midst of this, that is so important, but we get to be in our homes, with supplies, even in studio spaces. Incarcerated people do not have access to that same level of safety and control.

When we equate our experiences to prison, we are saying to those who carry the trauma of punitive systems that their pain is equal to ours. Staying home under blankets, with running water, art supplies, internet access, etc. This is a very different experience.

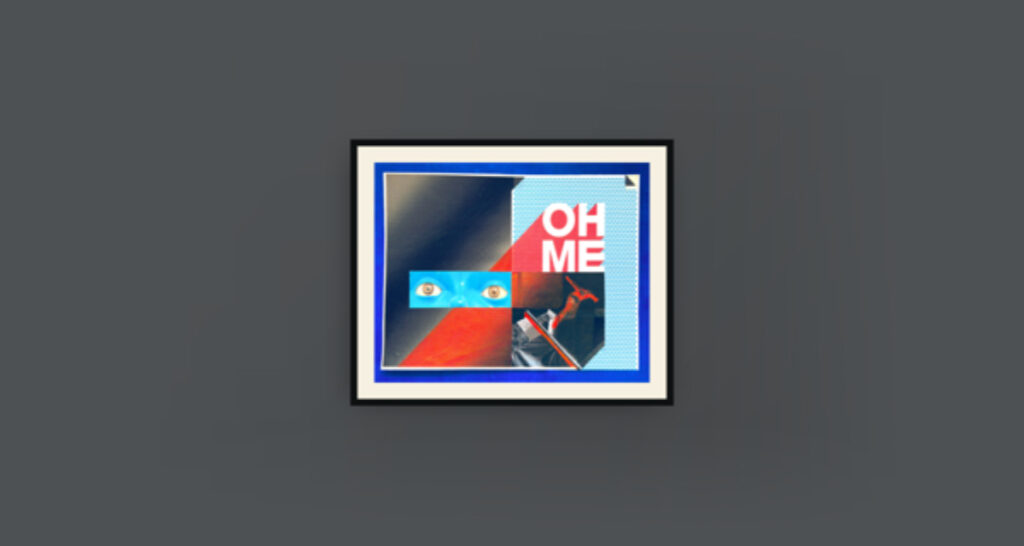

Now let’s not look past the very real emotions quarantine has presented us. Christine Mitrentse’s work in the show speaks about the struggles they’re facing, “the feeling of being near to a mental breakdown.” The work HOME is a screen printed collage that evokes feelings of the uncomfortable and escapism. The relentless eye contact coming from unnaturally blue colored eyes elicits uneasiness. The person jumping away between buildings provokes a sensation of escape. Fight or flight would be a deft phrase to describe the piece. This experience is real and valid and expresses this panicked call for help without having to allude to anyone else’s struggles. Mitrentse is going through it and says that. We are all having to cope with reality right now, this is a collective experience. What artists and curators need to remember is that when we say collective, it includes the people society often erases. We can say what we are feeling without having to trivialize another point of view, Mitrentse doesn’t!

When we listen to those who have been incarcerated, they have a wealth of knowledge to offer us in this waiting time. Shaka Senghor, during his 19 years spent in prison, worked towards being a “reliable witness” of the atrocities of American incarceration. In his feature on the Mindvalley Podcast, he says the first thing he wrote and accomplished was fiction. He points out the role of imagination in his coping with solitary confinement. To him, imagination, a central tool to any creative, is also an invaluable coping skill for hard times.

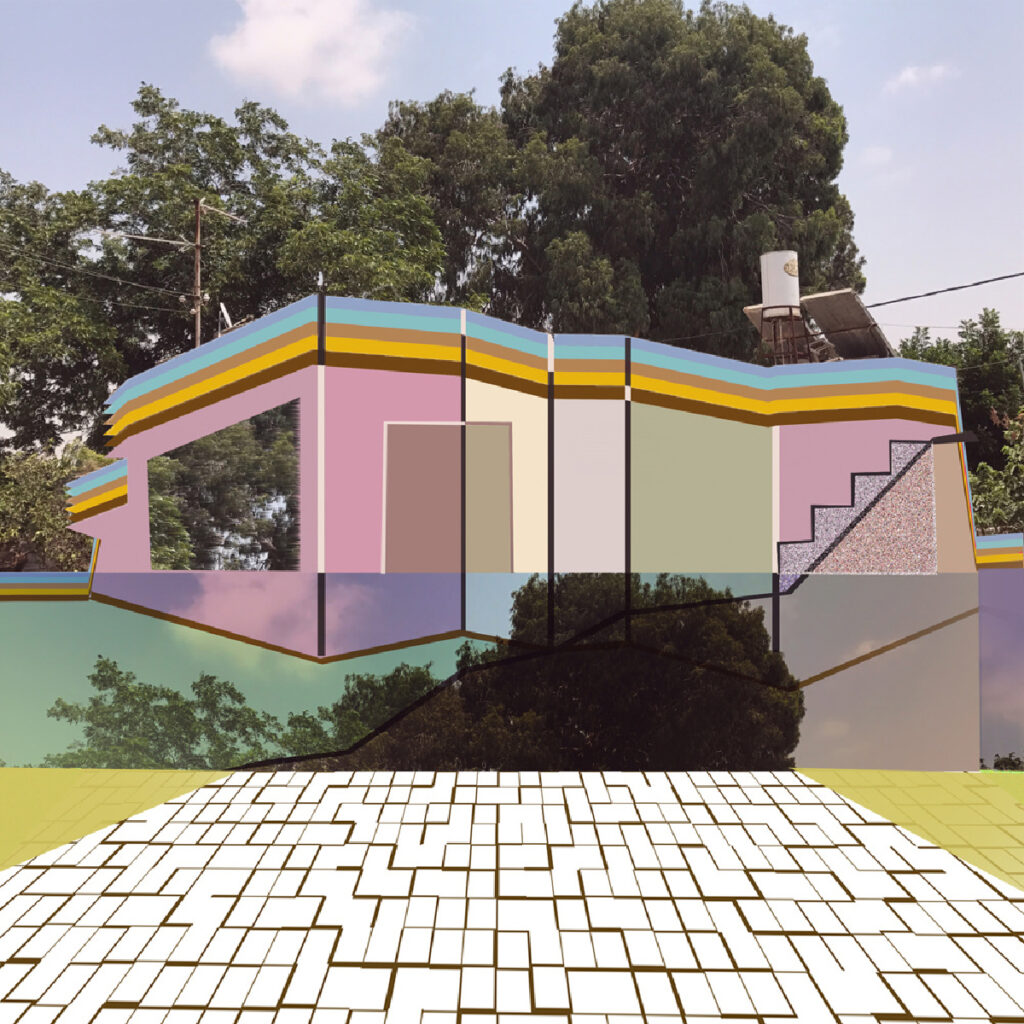

In this way, artists included by Preza also exhibit resilience through imagination. Works by Gal Cohen are fictional spaces that extract different people’s visions for a perfect quarantine house and make them real. Cohen depicts the ideal place to spend quarantine. This process alludes to the idea of a “happy place,” a mental retreat for when reality is overwhelming. Fun jubilant colors bounce off each other in Yael’s House of Dreams. The rectilinear house placed amid trees and powerlines is in tune with nature and society. The flat roof is reminiscent of houses in warmer and drier climates where snow and rain are not concerns. Rainbow trim on the little house adds liveliness and joy. This is a safe happy place to connect with and remember when current events shake us.

The inclusion of this work is more significant than Mazzillo’s, despite it not being in the same elevated room as Quarantine Day 65. It’s important because it shows the dissatisfaction with current circumstances and the alchemy used to transform. It is a call to imagine a place that doesn’t exist now but could. In a time where people are being called to brainstorm ways of protecting communities and seeking atonement, conceptualizing ideals is an invaluable tool. Instead of equating experiences, we can learn from others and way-find together.

Artists and creatives have a calling to create, to be learners and teachers of perspective and experience. This show highlighted an expansive point of view. It reflects the experiences of the world back onto itself: the hope, boredom, melancholy, and juvenescence that we are embodying at this moment. It challenges the viewer’s experience of time and age. This exhibition also reflects ugly parts of culture to us. The ease in which we erase and equate the experiences of imprisoned people who are alongside us experiencing a global pandemic. We have a responsibility to each other to be stewards of visibility and care and in this way, Home, the exhibition, neglected to empathize with those who isolate and wait for freedom regardless of a pandemic.